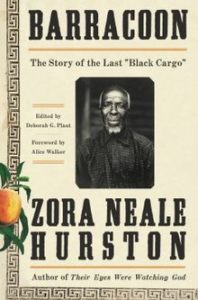

Book Review: Barracoon

Zora Neale Hurston’s “latest” work, Barracoon: The Story of the Last “Black Cargo,” is the most anticipated book of the year. It was one of the few books I have ever pre-purchased months ahead of time. And the book doesn’t disappoint! It should be required reading in all American high schools.

Zora Neale Hurston’s “latest” work, Barracoon: The Story of the Last “Black Cargo,” is the most anticipated book of the year. It was one of the few books I have ever pre-purchased months ahead of time. And the book doesn’t disappoint! It should be required reading in all American high schools.

Barracoon tells the little-known story of Cudjo Lewis or Kossola, the last known survivor of the Middle Passage. What makes this book so unique is that there are not many testimonies by survivors of the African Slave Trade, which officially ended, on paper at least, in 1808. The Middle Passage is the largest forced migration of humans in world history. It is estimated that over 12 million Africans were enslaved.

Of that number, there are only a small handful of slave narratives. The most notable one is by Olaudah Equiano, whose book, The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, was the driving force behind the Slave Trade Act of 1807, which essentially ended the British transatlantic slave trade.

Between 1808 and 1861, there were at least 100 attempts by slave traders to bring human cargo to the Americas that were captured to suppress illegal trading. However, slave trade patrolling was mostly unsuccessful because the United States didn’t have enough vessels to guard African coastlines and slave ships used sneaky ways to evade patrols like hoisting European flag on the boats. Up to an estimated 50,000 enslaved Africans were illegally imported into the United States after 1808.

One of the boats that evaded patrols was the Clotida, the schooner Lewis came to Mobile, Alabama on in 1860. The Clotida is believed to be the last known slave ship to bring Africans to the United States. Lewis came with approximately 150 other Africans from present-day Benin. This human cargo – the Barracoon – only came to America on a wager for $100 made by the Clotida’s ship maker Timothy Meaher, who thought he could successfully smuggle enslaved Africans by undermining the law.

Hurston originally wrote this book in 1927, but it wasn’t published until 2018 because it is largely Lewis speaking in broken English. Historically, publishers shy away from releasing work in vernacular language as it is not viewed as “standard” language. Being an anthropologist, Hurston studied traditional folklore and language of the African Diaspora. Her best-known work, Their Eyes Were Watching God, was also criticized for using vernacular black dialect by other black intellectuals at the time, like writer Richard Wright, who thought the book would make “white people laugh” at black people. There was also concern by this same black Inteligencia that Barracoon would highlight an unspoken truth that Africans sold other Africans into slavery.

So what if Lewis didn’t speak proper English? Does that make his harrowing story less valid? Absolutely not! I assume English wasn’t his first language and he wasn’t ever given proper English language education when he came to America as enslaved people weren’t allowed to learn how to read and write. Even after slavery was abolished, there were many attempts by racist whites during Reconstruction and Jim Crow to deny educational opportunities for black folks. He was a product of his environment, and it didn’t seem fair that the black bourgeoisie of the day to judge him as a poor reflection on the whole black race solely on his dialect.

Yes, at times it is hard to read, but it is Lewis’s truth that he is speaking, and that is why the book is so important. He gives very descriptive accounts about life in Benin, being on the slave ship, being enslaved in Alabama, his marriage and the tragedies that befell all his children. He seemed very unhappy for most of his life for obvious reasons. Although he was only a slave for five years, he never really adapted to life in America, and he was always yearning to go back to what he called the “Affriky soil.” Africatown in Mobile was established after the Civil War for descendants of the Clotida to build a community for themselves after a failed attempt to raise funds to go back to Africa. This self-contained community spoke their own language and maintained many African customs.

I guess what most struck me was Lewis died in 1935; less than a hundred years ago. In theory, slavery is still a recent memory in the American psyche. I hope that now Lewis can find some peace in death that his story is being told and can be used as a lesson about humanity for generations to come.