Bandung, Identity and Media Perceptions

A couple of weeks ago, journalist Howard French brought attention to an ongoing problem in American journalism regarding coverage – or lack thereof – of Africa and indirectly about the developing world in general. In his open letter to the American TV news magazine 60 Minutes, which was co-signed by dozens of other journalists and academics, French states that voices from the African continent are muted and reduced to racial stereotypes. He pointed to recent segments from the program that only interviewed “white saviors” and featured jungle animals. He also took issue with the fact that no actual Africans were interviewed for a 60 Minutes piece on Ebola.

When I was in journalism school, this reporting phenomenon was called coup and earthquake syndrome. The developing world is only covered by the Western media when there is a war, natural disaster, or some other atrocity in a biased manner. International news coverage is already bad in America. Still, when you add in the constant negative news from the developing world, it does a disservice to both the people who are covered and Western newsreaders.

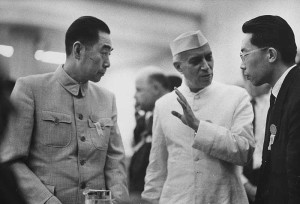

This month marks the 60th anniversary of the Bandung conference, an international meeting of 29 African and Asian countries in Indonesia. While this conference is today considered a minor bookmark in Cold War history, Bandung was significant in not only jump-starting the Non-Aligned Movement but also it was the first time the developing world had the opportunity to discuss a variety of social, economic, and political concerns in their own countries and have a voice on an international platform. While it might seem significant to see and hear from emerging African and Asian leaders, the Western media, for the most part, ignored the conference.

In 1955 most of the countries in attendance had recently become independent from their colonial rulers. They were starting to understand their role in a world divide by the capitalist United States and communist Russia.

Famed American writer Richard Wright was intrigued by this mass gathering representing over one billion people of color. As a black man who lived in the Jim Crow South and wrote about his experiences in Black Boy and Native Son, Wright believed that African Americans, Africans, and Asians shared the same common suffering of racism, colonialism, and mental slavery.

Famed American writer Richard Wright was intrigued by this mass gathering representing over one billion people of color. As a black man who lived in the Jim Crow South and wrote about his experiences in Black Boy and Native Son, Wright believed that African Americans, Africans, and Asians shared the same common suffering of racism, colonialism, and mental slavery.

Wright once said in a 1947 interview that a Black person in America “is intrinsically a colonial subject, but one who lives not in China, India, or Africa, but next door to his conquerors, attending their schools, fighting their wars, and laboring in their factories. The American Negro problem, therefore, is but a facet of the global problem that splits the world into two: handicraft vs. mass production; family vs. the individual; tradition vs. progress; personality vs. collectivity; the East (the colonial people) vs. the West (exploiters of the world).”

With a growing interest in global affairs regarding race and identity politics, Wright decided to attend Bandung as a credentialed journalist representing the anti-communist Congress of Cultural Freedom. He wrote a series of essays about his trip, which were subsequently turned into his book The Color Curtain: A Report on the Bandung Conference.

I recently reread this book and found Wright to be an amazing journalist and storyteller. The Color Curtain is possibly the most comprehensive media coverage about Bandung simply because Wright actually interviewed conference attendees and, thus, was able to capture the gathering’s true essence and nature. I highly recommend reading it!

Throughout his writings, Wright talks to Indonesians and other Asians from various life experiences about what the conference meant to them in the post-colonial context. He talked to them about their views on family, religion, education, and politics in Indonesia and their former colonial rulers in the Netherlands. What you learn from the interviews is that racial and class identity mean different things to different interviewees. The idea of a particular race and identity is not confined to specific countries or regions.

Wright also talked about other interesting people he met in Bandung. One story from his book that stood out to me was when he talked to a white American woman who was scared of her black American female roommate. The white woman thought the black woman got up in the middle of the night to practice voodoo using a “blue light” wand and spent an hour in the bathroom and came out lighter-skinned. When Wright probed the scared woman further, he realized that the black woman was most likely straightening her kinky hair with a hot comb and applying skin lightening cream, and didn’t want the white woman to see her real black self. Wright found it amazing that at a conference designed to address racism, the white woman reduced the black woman to a racial stereotype. The black woman felt she had to change her natural appearance to fit Western beauty standards because of her own mental colonialism.

In his interviews, Wright found that all the attendees had high hopes and dreams for their new future. Bandung had a full agenda, with discussions about racism in South Africa, colonial tensions between France and North Africa, the Palestine question, and if China, India, and Egypt were allying. However, if you only read the limited coverage from the Western media at the time about the conference, you would have had a different impression.

The United States refused to officially recognize the conference, citing that it was a gathering to recruit more countries into adopting communism. U.S. Secretary of State John Foster Dulles said this in a radio interview in March 1955: “Three of the Asian parties to the Pacific Charter, Pakistan, the Philippines, and Thailand, may shortly be meeting with other Asian countries at a so-called Afro-Asian conference.” The U.S. government then began a larger propaganda campaign in the media against the conference.

Much was said at the time about “Red” China’s presence at Bandung and it’s communist “intentions.” But if you read The Color Curtain, you find out the intentions were far from the political Left. A couple of Wright’s interviewees said bluntly that a communism infusion in Indonesia would be somewhat impossible since 90 percent of the country is Muslim. Most of the other countries represented at the conference were also deeply religious – Hindu, Muslim, Buddhist, Shintoist, Christian – and their religions conflicted with atheist communism. Even China recognized that it had to address the conference differently, mainly because of the religious and cultural differences throughout Asia and Africa.

The Western media also focused on the “problem” of excluding white delegates at the conference, which is interesting since non-whites were always excluded from such discussions about their own countries during colonialism. Wright wrote about how the world’s media covered Bandung, including quoting British journalist and government propagandist Sefton Delmar who said that the conference was a “political jamboree” that was “very exclusive and colour conscious.”

From the Examiner of Tasmania (Australia), December 1954: “Their invitation to twenty-five nations, including Communist China, but excluding all Western countries, to a conference in April, could be the beginning of an upsurge of racial hatred against the West.” Newsweek compared Bandung to the impending “Yellow Peril,” as it foresaw a global African-Asian menace’s formation.

But not all the media coverage was bad. The Christian Science Monitor said this: “… The West is excluded. Emphasis is on the colored nations of the world. And for Asia, it means that at last, the destiny of Asia is being determined in Asia, and not in Geneva, or Paris, or London or Washington. Colonialism is out. Hands-off is the word. Asia is free. This is perhaps the great historic event of our century.”

At the end of the conference, a communique was created, with the attendees addressing their grievances to the Western world. While the communique had the best intentions and sounded great on paper, even Wright admits that some of the grievances would be harder to address because of their complexity. Wright interviewed an MIT social scientist who believed that tangibles like economic development and international trade would be easier to help build bridges between the Western world and the former colonial world. However, intangibles like attitudes and perceptions will be harder to break for both worlds. This is why there is still this awkwardness and bias about how the Western media covers the developing world today. Perceptions, stereotypes, and attitudes are hard to break.

Wright said this about the media in 1955, which is still relevant in 2015:

“It was strange, but, in this age of swift communication, one had to travel thousands of miles to get a set of straight, simple facts. One of the greatest ironies of the twentieth century is that when communication has reached its zenith, when the human voice can encircle the globe in a matter of seconds when a man can project the image of his face thousands of miles, it is almost impossible to know with any degree of accuracy the truth of a political situation only a hundred miles distant! Propaganda jams the media of communication.”