Are African Americans Guilty of Cultural Appropriation?

I was reminded recently of a valuable lesson about understanding and respecting other cultures. I went on another business trip to Washington DC a few weeks ago and had some time to catch up with my business partner Marjane, who splits here time between DC and Nairobi. She is a native Kenyan and she is always amazed at the differences between black Africans and African Americans.

I was reminded recently of a valuable lesson about understanding and respecting other cultures. I went on another business trip to Washington DC a few weeks ago and had some time to catch up with my business partner Marjane, who splits here time between DC and Nairobi. She is a native Kenyan and she is always amazed at the differences between black Africans and African Americans.

When I met her for lunch recently, Marjane was particularly riled up about the issue of cultural appropriation. No, I am not just talking about white people appropriating cornrows, hip-hop and other aspects of black culture. Marjane was talking about African Americans appropriating from African culture.

She began telling me about her recent encounter with a 20-something African-American woman who sported an Afro and wore a Kente cloth “inspired” sari and jewelry at some natural hair meetup. This woman had the audacity to tell Marjane that she wasn’t proud to be black because she straightened her hair.

Marjane responded by saying that she flat irons her hair because she likes how it looks straight and it is easier to manage. She also said that she certainly didn’t do this because she hates her blackness.

I always found the way some people in the natural hair “community” who harshly judge others who don’t share their same taste in hair texture as offensive and off-putting. Not that there isn’t merit to what this woman is saying to a certain extent. Black females have been pressured to mimic Western standards of beauty for many years. Because of this, many black females have felt ashamed of their hair. Luckily, these standards are slowly changing and black women are becoming more comfortable wearing their natural tresses. However, I don’t think black women should be judged by other black women negatively if they still choose to straighten their hair for whatever reason.

Furthermore, in my experience, many of these judgmental naturalistas tend to be not well-informed or educated about their own black heritage. As a matter of fact, Marjane was more offended that the African-American woman who was judging her hair texture didn’t seem to know anything about Africa. Marjane asked the woman where she got the Kente cloth she was wearing. The woman replied that she bought it at Wal-Mart (really!) and that “it looked like it was from Africa.” She then asked the woman why she was wearing it as a sari and asked if she was South Asian. The woman said she wasn’t South Asian and that she was wearing it as a sari because she liked the way it looked on her.

Marjane proceeded to go all the way in on this clueless woman!

As the story was retold to me by Marjane with a strong accent:

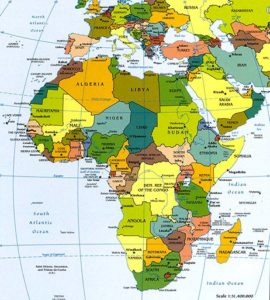

“I told this stupid woman she had no right to criticize my hair and she is walking about dressed the way she looks. She would be laughed out of all of Africa and India dressed the way she was. I told her that if she was going to wear African clothing, she should know where it is from in Africa. Africa is not a country; it is a continent of 54 countries with thousands of languages, ethnic groups, and cultures. Don’t just tell me it’s from Africa, woman! Kente cloth is from Ghana. Ashanti! Akan! West Africa! You are not Asian so why are you wearing a sari?”

Yeah, that really happened.

Marjane does make an excellent point. Just because you are black, doesn’t mean it is okay to appropriate from the cultures of other black people or other people of color for that matter, especially if you don’t know or understand the context you are appropriating. A recent example would be many of the attendees at this year’s AfroPunk Festival, which was a dizzying mess of appropriation. It’s great that African Americans want to reconnect with their lost African roots, but there is a right way and wrong way to do it.

I attribute my strong connection with diverse African cultures not just to my media development work in many African countries, but also because people of Caribbean descent have had a stronger relationship culturally with the African continent. From the maroon uprisings to Marcus Garvey’s Pan-Africanism, Jamaicans always take pride in their black heritage and connections to Africa. Some of the most conscientious African-American activists throughout recent history were of Caribbean descent like Shirley Chisholm, Stokley Carmichael, Louis Farrakhan and Malcolm X. Also, because slavery ended in most Caribbean islands well before America’s emancipation in 1865, many Caribbean folks have been able to retain their African roots better, and this can be seen in our music, fashion, hairstyles, cuisine, and storytelling.

With that said, I think we could all learn from this incident. Here are some tips I have learned over the years.

1. Know your history: If you truly want to be informed, or what the millennials say, “woke,” learn and know about the history and culture of Africa. In addition to reading books and watching educational programming to better understand your cultural identity, you should also talk to African people (and other people of color) and listen to and respect their histories.

2. Know what you are wearing: If I am wearing anything that is African inspired, I try to make sure I know the history behind it. For example, I like to wear box braids. If someone asks me about them, I will say they were done by a woman from Guinea, and box braids have their roots in many parts of Africa, including in Namibia, where Eembuvi braids were worn by women of the Mbalantu tribes.

3. Support African businesses: Instead of buying African products from a Western department store support an African business. I buy a lot of my handbags, jewelry and clothing from the Maasai market in Nairobi when I travel there. Of course, not everyone can travel to Africa to shop, but you can support a local African vendor so the money will go back to that black-owned business, and not a Western big box.

4. It’s not what you wear: it’s who you are: It really doesn’t matter how long your dreadlocks are or how good your Dashiki looks on you. At the end of the day, it is more important to know who you are as a person of African descent and how to pay respect to our ancestors for future generations.