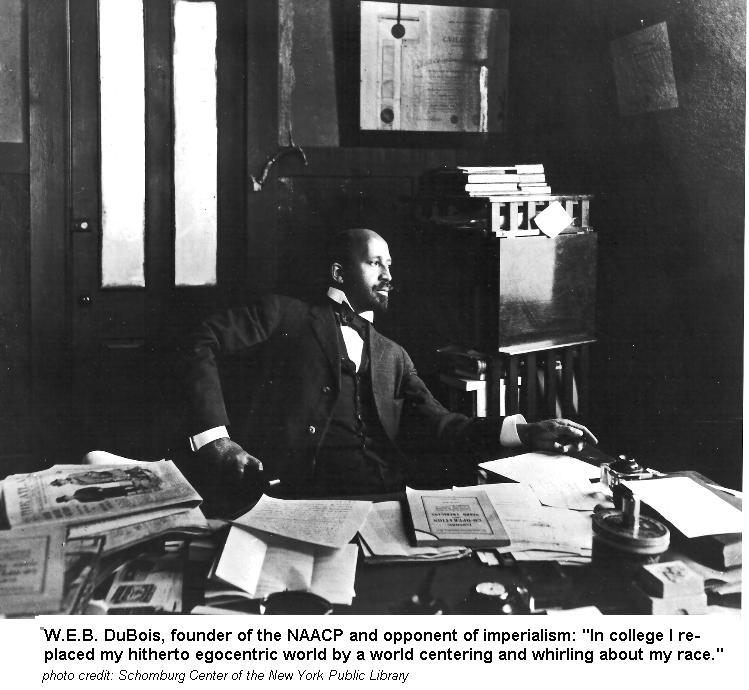

How W.E.B. Du Bois Used Innovative Communication To Advance Social Justice

I receive many free books to review for this site, but I don’t always have the time to read them unless I find a book that really speaks to me. I recently read A People’s Art History of the United States by Nicolas Lampert, which documents how art and visual communication shaped American social movements over the last four hundred years.

One chapter that caught my attention was about civil rights activist and journalist W.E.B. Du Bois. In 1910 when Du Bois became the director of publicity and research for the NAACP, he also became the editor for its monthly magazine, The Crisis. At the time, a growing number of lynchings were taking place throughout the South. According to the Tuskegee Institute, an estimated 4,724 people were lynched in the United States from 1882 to 1968, and two-thirds of them were African-American. Blacks were lynched for pretty much any “suspected” reason.

Du Bois used his platform at The Crisis to speak out about the killings. Using photographs and eyewitness accounts, The Crisis became the leading publication in the country that regularly reported lynchings.

Du Bois used his platform at The Crisis to speak out about the killings. Using photographs and eyewitness accounts, The Crisis became the leading publication in the country that regularly reported lynchings.

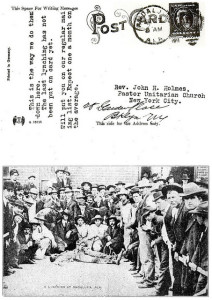

This postcard was published in the January 1912 edition of The Crisis. As was common at the time, photographers present at lynchings would process their images and print postcards on-site to sell to the crowd as “souvenirs.” This particular postcard was sent to anti-lynching advocate Rev. John Haynes Holmes to intimidate him. Du Bois reprinted the postcard in The Crisis to show the world the reality and prevalence of this horrific practice. At the time, it wasn’t common to see images of lynchings, even in the black press.

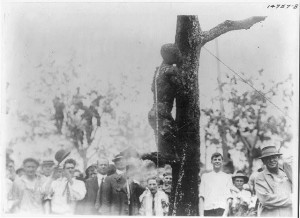

Du Bois also published lynching images of Jesse Washington (below), a mentally disabled black teenager in Waco, Texas, who was found guilty of raping and murdering a white woman. While Washington did confess to the murder, there was never any evidence that a rape had taken place. Following his conviction, Washington was castrated, mutilated, stabbed, and beaten before he was lynched. His body was then lowered into a fire, cut into pieces, and distributed as “souvenirs” to the crowd. As a finale, his torso was dragged through the streets.

The images are truly shocking, to say the least. But what is even more shocking is that photographers took pictures of the lynchings for profit, and then people would buy them to mail to friends like they were postcards from an exotic travel destination. This practice became so popular that in 1908 the U.S. Postmaster General banned mailing lynching postcards. It also speaks volumes about the low-value African-Americans had at the time.

The images are truly shocking, to say the least. But what is even more shocking is that photographers took pictures of the lynchings for profit, and then people would buy them to mail to friends like they were postcards from an exotic travel destination. This practice became so popular that in 1908 the U.S. Postmaster General banned mailing lynching postcards. It also speaks volumes about the low-value African-Americans had at the time.

This is why Du Bois was determined to publish and reappropriate the images. This was truly a case where images speak louder than words. “Let everyone read this and act,” Du Bois once said.

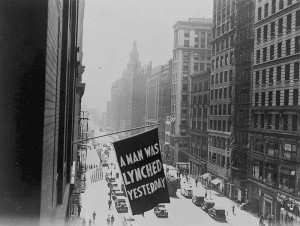

Du Bois also took his anti-lynching activism to the streets – literally. This flag hung outside the New York NAACP offices on Fifth Avenue. This image was the first thing that introduced me to the organization while learning about black history as a younger student. It was a brilliant way to bring attention to the crime to those in the North and establish an advocacy brand for the organization.

Du Bois also took his anti-lynching activism to the streets – literally. This flag hung outside the New York NAACP offices on Fifth Avenue. This image was the first thing that introduced me to the organization while learning about black history as a younger student. It was a brilliant way to bring attention to the crime to those in the North and establish an advocacy brand for the organization.

While he made a name for himself and The Crisis with the anti-lynching campaign, Du Bois also knew that to fight racism, and he had to counter it with positive images of successful African-Americans. This was largely driven by his controversial theory that the “talented tenth” percent of educated, middle-class blacks will guide the 90 percent of working-class blacks. He was also an early supporter of the Harlem Renaissance and frequently published Langston Hughes, Laura Wheeler Waring, Alan Locke, Countee Cullen, Claude McKay, and Romare Bearden.

Whether he was publishing images of an affluent black couple that just got married or putting on a silent march in solidarity with the East St. Louis race riots victims, Du Bois not only helped to change the way whites viewed African Americans but also how African Americans viewed themselves. Du Bois’ work at The Crisis is a major milestone for racial uplift for African-Americans and advocacy journalism.