Should White People Tell Black Stories?

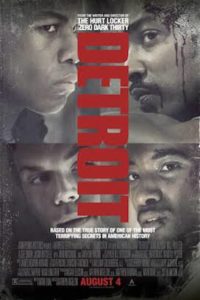

So I saw the movie Detroit a couple of weeks ago…

So I saw the movie Detroit a couple of weeks ago…

It’s not a horrible movie, BUT it was obvious from the very beginning of the film that director Katheryn Bigelow didn’t really have any black consultants in the room to tell her how to best tell this story with sensitivity and empathy. I can understand the complaints from other black viewers. This film brings up another conversation about whether white storytellers should tell black stories (or stories of other people of color for that matter).

I am of the belief that it doesn’t really matter what the skin color of the storyteller is; it is more important that the story is told with accuracy and respect. However, with that said, a black storyteller is going to have a completely different perspective on a historical, racial event than a white storyteller. This is why I think Bigelow fell short with this film. Maybe if she consulted with some knowledgeable black folks during the filming process, maybe the film could have been better.

This is not to say that if the film was made by a black director, it would have been automatically much better and on point. That black director could have been just as tone-deaf with the film. Nonetheless, more times than not, black directors do black stories better because of the perspective.

Take for instance Spike Lee’s epic film Malcolm X, which celebrates its 25th anniversary this year. There was a similar controversy during pre-production for this film. Originally, white Canadian director Norman Jewison was to direct the film. However, Lee and others in the black community protested that it should be made by a black director. Lee succeeded and took over as director and rewrote the script in his vision with support from black consultants and people who actually knew the slain leader. Coincidentally, some black leaders like Amiri Baraka were concerned about how Lee would make the film because he was a middle-class black man and Malcolm X represented inner-city, working-class blacks.

Lee also came up against budget restraints from Warner Bros who refused to increase funding for the film. Luckily, some very wealthy black folks like Oprah Winfrey, Bill Cosby, and Prince came through with funding so Lee could make the film he envisioned. When it was time to promote the film, Lee requested to only be interviewed by black journalists.

At the end of the day, Malcolm X was a great film not just because a black director made it, but because it was great storytelling. Before I first saw the film in the theater as a teenager, I didn’t know who Malcolm X was. But after seeing it, I was inspired to learn more about his life and other black leaders. While Norman Jewison did a great job directing In the Heat of the Night, I don’t think he would have been able to do justice to Malcolm X’s life because of the perspective. Also, black folks are very protective of how our leaders are portrayed in the media, due to the long history of sanitizing and white washing black history in this country. The black community was especially concerned about Malcolm X’s portrayal on film because of some of the controversial things he said about whites before leaving the Nation of Islam and if Jewison was going to make him look more sinister on film. It mattered to have the right person who would handle his life story with care and accuracy. I still catch Malcolm X whenever it comes on TV because it still stands the test of time and quality.

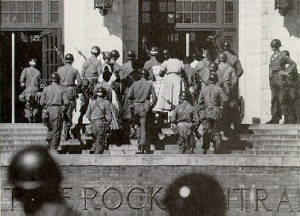

So going back to Bigelow’s Detroit, there was literally a problem with this film at the very beginning with an animated telling of the Great Migration. I assume this was done to give viewers a background on the history of race in the Motor City. But when I saw this, I thought it trivialized and diminished the story. I wasn’t sure if I was about to watch a cartoon about a very serious, hurtful event. Clearly, Bigelow had no black folks there to tell her “No, don’t do that.”

There was also the problem with John Boyega’s character, Melvin Dismukes, who was a security guard patrolling a supermarket who became like a peace negotiator at the Algiers Motel that night. If you didn’t know anything about Dismukes or the Algiers Motel incident, you wouldn’t understand why he was even in the film. But yet all the marketing for the film is focused on John Boyega, which is probably because he is the most well-known person in the film. But it still didn’t make any sense. It would have been better if Bigelow spent more time explaining Dismukes’s background.

Then there is this whole issue of torture in the film. Not surprised there was so much violence in it, as Bigelow is known for doing movies with lots of violence. Some black viewers complained about the excessive, graphic depictions of torture by the white police officers. However, if that level of violence is accurate to what really happened, then that is fine to show in my opinion. Again, I’m not for sanitizing history. Ironically, though, it seemed like the film’s violent treatment of the two white girls was less severe than was depicted in John Hersey’s book, which said that they were stripped completely naked and called n*gger lovers. It was obvious that the black guys at the motel were not being tortured because of a possible gun or sniper in the building, but rather because they were with white women. Something about the more violent punishments on black male bodies and no discussion on why one of the white women lied about Dismukes being a perpetrator turned off a lot of black viewers.

Maybe the real conversation we should be having here is how to get more qualified black directors and writers to create these black films. While #OscarSoWhite brought much-needed attention for more people of color in front of the cameras, we need to also focus on increasing diversity behind the cameras as well so there can be more balanced storytelling about us.